I saw The Shaggs Philosophy of the World at Playwrights Horizons on Wednesday (May 25, 2011), in its second preview performance. Based on a true story, The Shaggs describes how Dot, Betty, and Helen Wiggins, sisters from Fremont, NH, were coerced into becoming a band by their mercurial, rather psychotic father, Austin, whose plan for his daughters’ musical career came to him as a vision from his dead mother. The three young women had no musical training or interest before he pulled them out of high school, bought them two electric guitars and a drum set, and ordered them to learn to play. The musical traces their reluctant artistry and his increasingly crazy designs on their futures.

I saw The Shaggs Philosophy of the World at Playwrights Horizons on Wednesday (May 25, 2011), in its second preview performance. Based on a true story, The Shaggs describes how Dot, Betty, and Helen Wiggins, sisters from Fremont, NH, were coerced into becoming a band by their mercurial, rather psychotic father, Austin, whose plan for his daughters’ musical career came to him as a vision from his dead mother. The three young women had no musical training or interest before he pulled them out of high school, bought them two electric guitars and a drum set, and ordered them to learn to play. The musical traces their reluctant artistry and his increasingly crazy designs on their futures.

Austin uses all the family’s money to cut an album that gets no airplay, and tries to book gigs that take them nowhere, essentially because no one but him thinks his daughters are talented. The musical traces how each of the daughters suffers differently from the way his dreams constrain their own.

With a story by Joy Gregory (who wrote the book and lyrics), Gunnar Madsen (also music and lyrics), and John Langs (who also directed), The Shaggs is a fascinating, affecting show. The story would be entirely unlikely if it weren’t true. The frame puts Austin (Peter Friedman) in conversation a bit too often with his deceased mother to deliver the requisite exposition. But scenes among the sisters are full of nuance and heart, of hope for the potential of what they might become and sadness over what they know they really are. The family’s interactions with the amateur and professional music world convey the awkwardness of people from a small town in the 1960s trying to achieve stardom, a goal that only Austin truly desires.

Because the girls are teenagers when Austin’s plan begins to take shape, The Shaggs also illustrates how difficult it was for them to maintain normal childhoods. Betty (Sarah Sokolovic) tries to play up her feminine wiles but her advances are rejected by Kyle (Cory Michael Smith), the young man whose dream is to be, as he describes it, a cosmonaut. Kyle’s affections run to Helen (Emily Walton), the youngest Wiggin daughter, who’s infatuated with him in return.

Helen can’t quite see anything distinctive in her future. Even before her father sets them on their wrong-headed musical path, she decides she’ll distinguish herself by refusing to speak. Dot (Jamey Hood), the oldest, is most determined to please her father and bend to his will. Her ambivalence about his strange notions conflicts with her loyalty. (Her one solo is called “Don’t Say Nothing Bad About My Dad.”)

That each of the sisters is so clearly different from one another provides part of the musical’s charm. Hood, Sokolovic, and Walton do a beautiful job individually and as a trio, finding complicated allegiances and friction among the sisters while they suffer together their father’s sometimes harsh and isolating, utterly ineffectual training regimens.

In a repeated sight gag that describes how desperate Betty and Helen are to free themselves from their father’s tyranny, they leave the family home through a bedroom window, throwing themselves head first over the ledge and being whooshed out into the night. When Austin realizes their escape route and boards it up, their suffocating imprisonment is horrifying.

The Shaggs is a small show with a very consistent narrative and pop-musical tone. It evokes the stultifying environment of small town life, with its hierarchies and affectations and its community and camaraderie. Annie Golden is lovely as the beleaguered mother who wants to help her husband pursue his dreams, but can’t fathom his obsession with making their daughters famous. Walton brings sweetness to Helen’s silence and makes her mute expressions full of meaning and appeal. Smith is affecting as the earnest Kyle, who suffers his own injustices at Austin’s hands. Kevin Cahoon and Steve Routman, who rotate through various supporting male roles, bring just the right level of affectionate caricature to each one.

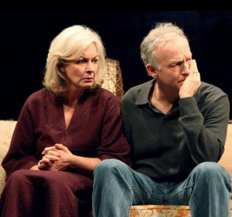

As Austin, Peter Friedman stretches out of his more typical abject characters into that of a forceful patriarch whose madness drives his family over the brink of disaster. Unfortunately, Austin’s obsession and brutality make him rather one-note; the daughters’ scenes are more compelling than those in which their father stokes his insanity.

Gregory, Madsen, and Langs also creatively solve the challenge of how to create a good musical about talent-poor musicians. The audience hears The Shaggs rehearsing and understands their unfortunate limitations. But when the girls enter the recording studio and Austin listens to them cut their demo tape, we hear them as he does, as sparkling, charismatic talents who can sing and play and even dance.

When the scene cuts to the recording engineers, listening to the band through the studio monitor, they hear them as they are—off key, uninspired, and performatively flat. Maintaining these two spheres of their musicianship throughout The Shaggs—the fantasy and the reality—allows the story to be told through the very idiom the band couldn’t quite master.

Ironically, Lester Bangs, writing for Rolling Stone, rediscovered The Shaggs in 1980, when punk rock created a context in which their atonal, affectless music made sense and even seemed radical. But in The Shaggs, for the Wiggins sisters, their father’s control over their lives can’t be redeemed. Even after his early death of a heart attack, they can’t shake loose his damaging legacy and the humiliation they suffered from his misbegotten dreams.

The Feminist Spectator

The Shaggs Philosophy of the World, Playwrights Horizons and New York Theatre Workshop, at Playwrights Horizons. Opens June 7, 2011.