The status of women directors has received relatively less airtime and press space compared to the perennial woe expressed over the paucity of women playwrights represented on Broadway (or Off, for that matter) and in regional theatre seasons.

Patrick Healy’s recent New York Times article, “Staging a Sisterhood” (2/3/11 issue, print edition), draws important notice to a crop of women now working more frequently on higher profile productions. Wonderful artists like Leigh Silverman (Chinglish and the upcoming The Madrid, with Edie Falco), Anne Kauffman (Detroit), Pam MacKinnon (Clybourne Park and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf), Anna D. Shapiro (August: Osage County), Rebecca Taichman (Luck of the Irish), and many more seem to be finding their way into broader public consciousness, often by collaborating with the host of talented women playwrights now populating the American theatre scene. Annie Baker, Amy Herzog, Kirsten Greenidge, Bathsheba Doran, Madeline George, Katori Hall, Lisa D’Amour, Lisa Kron, Lydia Diamond, Tanya Barfield, and many more women writers are galvanizing audiences with their stories and widening our sense of how theatrical narrative works and the people on whom it can focus.

But when Roundabout Theatre’s Artistic Director Todd Haimes tells Healy, “I don’t feel an old boy’s club exists any more,” I fear he’s being disingenuous, even though he admits, “but statistics might disagree.” While the women interviewed for Healy’s article paint a generally hopeful picture of their career prospects (only Tina Landau, who most recently directed Paula Vogel’s Civil War Christmas at New York Theatre Workshop, calls directing a “male-dominated tradition”), let’s admit it: the glass ceiling persists.

But when Roundabout Theatre’s Artistic Director Todd Haimes tells Healy, “I don’t feel an old boy’s club exists any more,” I fear he’s being disingenuous, even though he admits, “but statistics might disagree.” While the women interviewed for Healy’s article paint a generally hopeful picture of their career prospects (only Tina Landau, who most recently directed Paula Vogel’s Civil War Christmas at New York Theatre Workshop, calls directing a “male-dominated tradition”), let’s admit it: the glass ceiling persists.

“’Can we call it growth when we say the 2011-12 season saw three women directing plays on Broadway as opposed to one woman in 2001-02?’ asked Laura Penn, executive director of the union representing stage directors and choreographers.” (Healy, NYT, 2/3/13)

No, we frankly can’t call it growth. Is the current “trend” a happy bubble that will burst at the next sign of recession, when producers worry about declining profits and fear they can’t entrust women with their budgets? And if women directors’ fortunes are tied to those of the talented women playwrights with whom they collaborate, can we ignore the statistics that continue to track these playwrights’ compromised, constrained successes, which rarely happen on Broadway? Theresa Rebeck remains the only woman playwright able to open a play on Broadway without years of development workshops and productions that move from Off-Off to Off- to maybe London to, on the rare occasion for playwrights who aren’t Rebeck (or Wendy Wasserstein before her), Broadway.

The New York Times also reports that stars like Al Pacino and Scarlett Johansson increasingly wield the real power to bring shows to Broadway, but are mostly interested in revivals that allow them to attempt the roles they’ve long wanted to play. Pacino felt he was ready to take on Shelly Levene in David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross and Johansson, too, said “now felt like the right time for me” to play Maggie in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof; both are now starring in Broadway revivals. Because Pacino got a hankering to do Mamet, producer Jeffrey Richards bumped his planned Broadway production of Lisa D’Amour’s Detroit, which was produced (beautifully) last fall at Playwrights Horizons instead.

The New York Times also reports that stars like Al Pacino and Scarlett Johansson increasingly wield the real power to bring shows to Broadway, but are mostly interested in revivals that allow them to attempt the roles they’ve long wanted to play. Pacino felt he was ready to take on Shelly Levene in David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross and Johansson, too, said “now felt like the right time for me” to play Maggie in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof; both are now starring in Broadway revivals. Because Pacino got a hankering to do Mamet, producer Jeffrey Richards bumped his planned Broadway production of Lisa D’Amour’s Detroit, which was produced (beautifully) last fall at Playwrights Horizons instead.

What does this “star casting” trend mean for plays by women and their collaborating women directors? Richards admitted it was much easier to raise the requisite money to do Mamet, with Pacino in the lead, than it was to finance Detroit. And the Times article underlines how much power these stars accrue given how hungry producers are for hits in an economic environment in which only 25% of Broadway productions turn a profit. Which producers will risk new plays without star casts–especially those written and directed by women?

What does this “star casting” trend mean for plays by women and their collaborating women directors? Richards admitted it was much easier to raise the requisite money to do Mamet, with Pacino in the lead, than it was to finance Detroit. And the Times article underlines how much power these stars accrue given how hungry producers are for hits in an economic environment in which only 25% of Broadway productions turn a profit. Which producers will risk new plays without star casts–especially those written and directed by women?

Women directors who run theatres perhaps have a bit more sway. Healy cites for example Lynn Meadow at Manhattan Theatre Club and Sarah Benson at Soho Rep. Scanning the regional theatres, we could also mention Diane Paulus, who is interviewed in Healy’s article and directs on Broadway mostly by transferring productions from ART, the theatre she runs in Cambridge. Emily Mann, the longtime artistic director at Princeton’s McCarter Theatre, transferred Having Our Say in 1995 (receiving three Tony nominations in the process) and recently directed Streetcar Named Desire with an African American cast on Broadway. Garry Hynes and Mary Zimmerman, two of the handful of women who’ve ever won the Tony for Best Director, both transferred to Broadway productions they developed with their own companies (the Druid and the Lookingglass, respectively, for Beauty Queen of Leenane and Metamorphosis).

Women directors who run theatres perhaps have a bit more sway. Healy cites for example Lynn Meadow at Manhattan Theatre Club and Sarah Benson at Soho Rep. Scanning the regional theatres, we could also mention Diane Paulus, who is interviewed in Healy’s article and directs on Broadway mostly by transferring productions from ART, the theatre she runs in Cambridge. Emily Mann, the longtime artistic director at Princeton’s McCarter Theatre, transferred Having Our Say in 1995 (receiving three Tony nominations in the process) and recently directed Streetcar Named Desire with an African American cast on Broadway. Garry Hynes and Mary Zimmerman, two of the handful of women who’ve ever won the Tony for Best Director, both transferred to Broadway productions they developed with their own companies (the Druid and the Lookingglass, respectively, for Beauty Queen of Leenane and Metamorphosis).

Women directing new plays somehow seems a natural fit, but how often do we see women directing the canon, especially on Broadway? Karin Coonrod has directed in the Public Theatre’s Shakespeare cycle and mounted classics at ART, but for Broadway, Daniel Sullivan gets the nod (Merchant of Venice). Susan Stroman and Kathleen Marshall can successfully direct Broadway musicals, probably because they’re primarily known as choreographers, which is a more gender-neutral or even female-friendly field. But they’ve never, to my knowledge, crossed over to direct straight plays (certainly not on Broadway).

The high profile Julie Taymor/Spiderman: Turn Off the Dark debacle haunts this scene, too. I don’t think Taymor’s plight caused problems for women theatre directors, but it underlined the issues that already exist. Taymor is enormously talented, a truly visionary theatre and film artist. But the Spiderman producers got away with calling her “difficult” and “emotional” in ways that would never pertain to a male director, even if he was being stubborn and highhanded and running millions of dollars over budget. Gender stereotypes continue to haunt women theatre artists of all stripes in ways that keep that glass ceiling hovering low.

The high profile Julie Taymor/Spiderman: Turn Off the Dark debacle haunts this scene, too. I don’t think Taymor’s plight caused problems for women theatre directors, but it underlined the issues that already exist. Taymor is enormously talented, a truly visionary theatre and film artist. But the Spiderman producers got away with calling her “difficult” and “emotional” in ways that would never pertain to a male director, even if he was being stubborn and highhanded and running millions of dollars over budget. Gender stereotypes continue to haunt women theatre artists of all stripes in ways that keep that glass ceiling hovering low.

For those of us interested in innovative theatre; in plays that tell new stories in new ways; in directors with a visual sense that makes something vivid and new out of the old proscenium stage, Broadway might not be the best place to expect the women artists we admire to succeed. But the resources available on Broadway, not to mention the salaries, working conditions, benefits, and essential visibility, make it difficult for women directors, playwrights, and designers not to aspire to those mid-town stages.

As Healy’s article demonstrates, women directors and playwrights are flourishing elsewhere, as they have for so long. I loved writer/director Tina Satters’ Seagull (Thinking of you) at the New Ohio Theatre during January’s Coil Festival in New York. Satter created stunningly original stage pictures, and her colloquial, queer adaptation of Chekhov’s play sounded poignant and new, performed by a female and gender-ambiguous cast that she directed with warmth and empathy. I’d be delighted to see Satter write and direct in a large, resource-rich forum like Broadway.

I also love the work created by Page 73, and the now-disbanded 13P, and the thriving, determined Clubbed Thumb, and the increasingly well-received, significant, venerable Women’s Project. Their production of Laura Marks’s Bethany, directed by Gaye Taylor Upchurch at City Center, is a smart, beautifully executed production of a play with a razor sharp, feminist critique of the American economy. The Women’s Project even makes its own bid for star casting in Bethany, with America Ferrera (of TV’s Ugly Betty fame) proving her stage chops in the leading role. Why doesn’t this production transfer to Broadway?

I also love the work created by Page 73, and the now-disbanded 13P, and the thriving, determined Clubbed Thumb, and the increasingly well-received, significant, venerable Women’s Project. Their production of Laura Marks’s Bethany, directed by Gaye Taylor Upchurch at City Center, is a smart, beautifully executed production of a play with a razor sharp, feminist critique of the American economy. The Women’s Project even makes its own bid for star casting in Bethany, with America Ferrera (of TV’s Ugly Betty fame) proving her stage chops in the leading role. Why doesn’t this production transfer to Broadway?

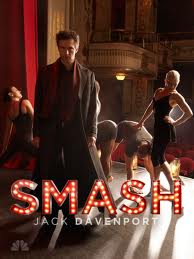

Like it or not, even in 2013, our stereotypes of “the theatre director” continue to be male. Smash, the NBC TV series created by Theresa Rebeck, began its second season last night. The preview press touted its new show runner, Josh Safran, fresh from Gossip Girl, and promised a new and improved run of episodes. But all the old tired theatre stereotypes persist so far. Derek (Jack Davenport), the mercurial director of Bombshell, the musical suffering development hell, gets called out for sexually harassing his cast members, after bedding one would-be leading lady and then almost seducing the other. He’s “the director” writ large, the auteur whose vision won’t be tamed; the cruel taskmaster whose exacting standards “get” the requisite performances from his women, even after he makes them cry; and of course he’s white, male, and heterosexual.

This stereotype isn’t true–we know that all Broadway directors aren’t Derek. But the point is that the stereotype persists. When people think of a Broadway director, the image of someone like Derek is already there, intractable, resisting efforts to erase it or to remake it into something more diverse. Those stereotypes can be very persuasive in the imaginations of people bankrolling risky, expensive projects.

This stereotype isn’t true–we know that all Broadway directors aren’t Derek. But the point is that the stereotype persists. When people think of a Broadway director, the image of someone like Derek is already there, intractable, resisting efforts to erase it or to remake it into something more diverse. Those stereotypes can be very persuasive in the imaginations of people bankrolling risky, expensive projects.

It’s not that women directors don’t have the pedigree. Of the directors profiled in Eric Grode’s sidebar, “Meet the Directors,” which accompanies Healy’s Times article, many refer to graduate degrees from Yale School of Drama or NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. These women have impeccable credentials and they’re impressively talented. What else could explain their relative lack of power and Broadway exposure but the glass ceiling?

Don’t you wish we could retire that old metaphor? Don’t you wish the glass ceiling would shatter like a trick stage prop, never to be reassembled? Without that barrier, what kinds of stratospheric success might women directors and playwrights accomplish? Wouldn’t it be great to know?

Imagine if women were employed regularly and visibly at all levels of American theatre. Imagine if they were routinely trusted to share their talent, their vision, their methods, their dramaturgical skill, and their emotional, political, and intellectual acuity. How might American theatre change?

Of course, many of us have been practicing that “what if” exercise for decades. Are we still stuck here, excited about articles that feature women we’ve followed for years? Wouldn’t it be something if we didn’t have to applaud simple attention to women, if their theatre work was expected, typical, unremarkable? If we could just talk about the work, instead of about the fact that it’s been produced at all? Years ago, I wrote a piece that took an ungenerous swipe at Julia Miles, the founder and then artistic director of the Women’s Project, because she imagined a time when her theatre’s advocacy for women would no longer be necessary. Decades later, I have to say I know what she meant–and I agree.

Would that companies like the Women’s Project could persist not because they have to, but because they want to continue creating fertile space for women theatre artists to learn and grow. Would that the glass ceiling could be smashed and replaced by a ladder on which successful women would help one another into positions of increased power and visibility and that they could all stay there and thrive. Would that the persistently unequal demographics that describe the gender (let alone race and ethnicity) of those working in the theatre would finally balance out, so that we wouldn’t be so thankful for just a few women’s successes. 50/50 in 2020 indeed.

Call me liberal; call me utopian; call me, maybe. Or call me a feminist critic on a life-long mission that’s not over, yet.

The Feminist Spectator

Jill, thank you for creating a vital picture of the current scene about women directors! I have also always been underwhelmed by how few female artistic directors hire female directors…. We just had a great talk at Muhlenberg by Prof. Omi Jones all about how to be an ally. We need to keep our alliances active and our awareness tuned in and up. B. Schachter

While you’re on the subject of wonderful women directors, I must direct your attention to Rachel Klein. She is one of the most innovative theatre artists I have ever worked with, is known in the downtown theatre circles, but gets very little attention elsewhere: http://www.rachelkleinproductions.com

As always, a very rich read!

All the best,

JpB

Is anyone going to mention Wendy Goldberg in all of this? It’s crazy toe that no one has featured get work turning The O’Neill around (and winning a Tony for those efforts) and her directing cred.

I’m in general agreement with everything you write here, but I want to pose one alternative to the “glass ceiling” explanation of why well-credentialed, talented women of the theater may not be directing on Broadway. That is, they are choosing to work in the well-established alternatives to what is largely a moribund subdivision of the entertainment industry. I don’t deny that a glass ceiling exists–far from it–but I measure the success of women in our art form more in relation to their artistic successes than their commercial triumphs, as I suspect you do as well. So I want to suggest that we re-imagine the “levels” in the topography of our field (if there must be strata) more in relation to creative power than boffo box office.